I’ve been a fan of Cameron Sharp’s work for a few years now, so when I heard

about his exhibition at the Coburn I knew I wanted to write about it. I arrived with my

camera in hand, prepared to capture images of his

Work, to sniff out threads of narrative, and give voice to the unspoken tensions at

work within the Work.

While shooting the Work I overheard a professor mention that a fellow professor

would not be attending the reception because they (speaking of Sharp’s work) “did not

care to see someone with no talent try to paint like Rauschenberg.” I thought this was a

bit harsh, but it does raise some crucial issues about Sharp’s Work. It also lends a fire of

indignation to my defense of the Work.

Before my reprisal, a brief aside: Professors are granted privilege, power, and

control over the contemporary discourse of art. I’d like to warn against using that power

to make discernments without first putting in the work of active viewing. The University

is no place for purveyors of lazy opinion. It is a place for careful ‘readers’, decipherers of

subtle scents, and defenders of what is sacrosanct in human experience.

_________________________________________________________________________

“In front of the photograph of my mother as a child,

I tell myself: she is going to die: I shudder…over a

catastrophe which has already occurred. Whether or

not the subject is already dead, every photograph is

this catastrophe.” ― Roland Barthes

I believe the Professor is circulating lazy opinions because it takes about three

honest seconds to determine that Rauschenberg would never have chosen the subject

matter that Sharp has chosen. It must be admitted that there are overwhelming material

and stylistic similarities: The saturation of the paint, though not hue. The boldness with

which Sharp applies the paint is at times damn near a ‘quotation’ of Rauschenberg. A

few of Sharp’s sculptural decisions –I’m thinking of the necklace dangling in the mouth

of the cardboard box in “WHEN WE ARE NOT TALKING (Self Portrait as a

Professional)” also seem particularly Rauschenbergian. Due to these family

resemblances, are we supposed to dismiss the Work as mere plagiarism? In the

contemporary climate, where pastiche is the name of the game, I’m inclined to assume

that Sharp has a good reason for quoting Rauschenberg. So what is the reason?

Rauschenberg began producing his Combines in the midst of Jackson Pollock and

abstract expressionism. Weary of the concept of canvas-as-stage-for-primal-performance

and the ideal of the solipsistic genius, which Pollock and other manly-modernist

promoted, Rauschenberg was intent from the outset to keep his ‘self’ out of the Work. To

prevent his Combines from lapsing into the realm of psychological investigation,

Rauschenberg appropriated images already at large in the cultural context of the 1950’s

and collected random, impersonal detritus from the street. He worked deliberately to

prevent overt narratives from taking shape. His goal seemed to be to create without

authoring; to offer an impersonal vocabulary that longed to be ‘read’ while

simultaneously thwarting the viewer’s attempts to ‘read’. Somewhere in this push/pull I

come to rest and delight in the simple physicality of Rauschenberg’s work. His approach

anticipated Barthes essay “The Death of the Author” (1967), which argues that authorial

intent does not arrest the meaning of a text or work of art. The Work achieves autonomy

when it enters the world, but this autonomy is a sort of agnosticism. Agnostic because

apart from a reader the Work has no meaning, but the Work carries within its cipher the

potential for all meaning. Simply said, each reader brings their own interpretation to the

text, but none has authorial privilege—least of all the author. There are no authors, only

readers. In this way every act of ‘reading’ signifies the ‘death’ of a previous

author/reader.

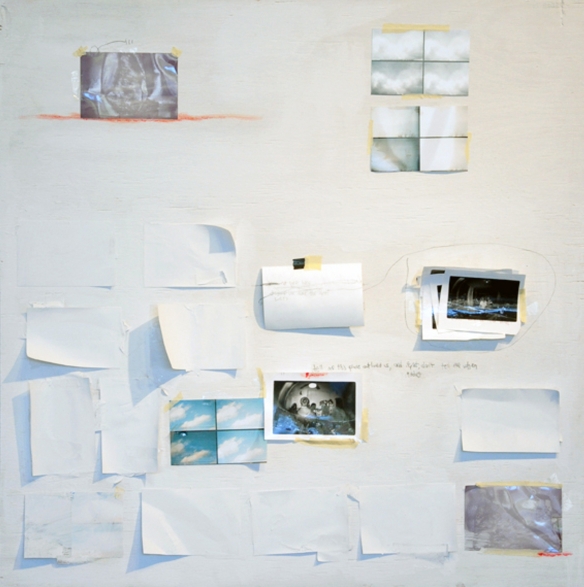

This, I believe, is why Sharp unabashedly “quotes” Rauschenberg, as a kind of

shorthand that lays out the rules by which his own Work will proceed. By “quoting”

Rauschenberg, he is also “quoting” an entire post-structural methodology. It’s not

plagiarism, but a portal of entrance into the work. Unlike Rauschenberg’s impersonal

subject matter, Sharp works with materials that are intimate and self-conscious:

photographs from his own life—often of his own family, handwritten notes from his

professional life as a gallery coordinator, a necklace (whose?), a roll of masking tape (his

primary means of holding these tenuous assemblages together). These materials are

mundane, yet poignantly his own. I see his use of simple, unembellished materials as a

grand democratic gesture. Of course, found and recycled objects are the trope of our day,

but artist usually take care to transform these materials into something unrecognizable—

to transcend the trash-ness. Sharp drops these pretenses. Because his Work is composed from the same sad dross that fills our own desk drawers, the materiality itself is a direct challenge to the viewer. He says to us, “This is what you need: a bent-ass piece of ¼ inch plywood, some tape, photos shot on a camera anyone can afford, mis-tinted house paint, and your memories. Now get to work!”

Sharp’s formal training is in photography, so we can’t overlook what the

photograph means to him. His work seems to call into question the hierarchy of the

photograph itself. The photograph parades around as if it’s the real. It purports to Be the

world, to Be present, constructive, whole. But there is a laceration between the world and

the photograph; a wound between the memory (never re-livable) and the archive (always present). The work seems born out of the same desperation that compels us to slavishly record everything and immediately stuff the photos in boxes, not wanting to be reminded of what we’ve lost. It is no coincidence that Sharp’s images are usually family scenes. Happy. Silent. Unremarkable. The photos are grainy, which makes them feel older than they are, as if the future has outpaced them (I can date them by matching referents that pop up in my own relatively recent and much more vivid digital images). In this way the

scenes, the subjects themselves, seem already pregnant with their own absence. A whole

family attuned to the tyranny of the clock’s hand. A whole family that senses their death

has just been written there.

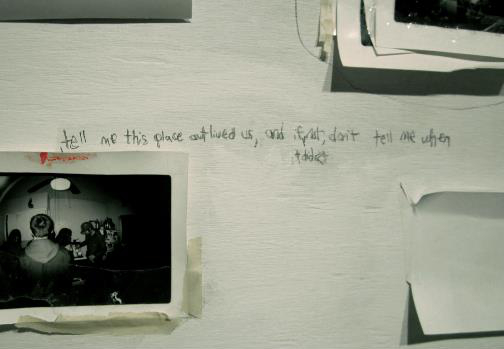

Cameron Sharp

Detail from SAME AGAIN

“tell me this place outlived us, and if not, don’t tell me when.”

^

it did

Sharp uses film-based point-and-shoot cameras, which suffer from a slight

discrepancy between the image seen through the viewfinder and the image that actually

passes through the lens. This discrepancy may be small, but the philosophic

consequences are huge in Sharp’s work. To exaggerate this discrepancy Sharp often

disregards the viewfinder altogether, shooting from the hip (see his fabricated,

viewfinderless camera in “To The Mark”). It’s as if he wishes to remove himself-as author,

and in distancing himself gain immunity from the laceration between the memory

(in which he’s a present and willing participant) and the archive (which he is compelled

to make, despite the wound the photo will inflict). I have the thought, illogical but

accurate, that Sharp is making anti-photographs.

It is exhilarating to me that a man who seems to suffer the ‘wound’ of the

photograph so succinctly cannot help but wrestle with the photograph. It is precisely here

that Sharp differs from Rauschenberg. Whereas Rauschenberg started with impersonal

images and borrowed symbols in order to keep his self out of the work, Sharp begins with

his self and actively—brush in hand, with strong, aggressive marks— attempts to write

himself out of the Work he has created. There are bare nails where photographs used to

hang (as if the Work is never finished for Sharp, but a thing that morphs with time; as

fluid as memory itself). He scrawls messages haphazardly across the surface. Some of these messages set out in pursuit of great insight, only to trail off unresolved. His work is stuffed with temporal markers: date/date/date. He guides us in our viewing—or

perhaps misguides—with playbook-like marks. He applies a photograph, obscures it. He

paints out subjects completely. What subjects do remain do so tenuously. I have the

sensation I must not avert my gaze or what remains of the subjects—the evidence of their

lives—will be completely washed over.

It is insincere to accuse Sharp’s Work of failing on account of its references to

Rauschenberg or because of his use of unadorned, honest materials –for these are the

very rules by which the work operates. The failure has to come from within the work.

And indeed, there are a few pieces that seem to fail on account of Sharp’s own

methodology. When Sharp is at his best there is a heroic dissidence between the intimate

nature of the photographic narratives and the intensely physical and iconoclastic mark

making. At his worst I sense (a) timidity and an unwillingness to relinquish the authority

of the photograph, or (b) an overall lack of photographic/narrative tension. One thing that

I believe is undeniable is that the work is full of heart and brimming with a nuance that is

all Cameron Sharp.

© Jason Kaufman 2013

_________________________________________________________________________

Cameron Sharp is an artist living in Mansfield, Ohio who uses issues of memory, time, family, and space as springboards to examine greater interpersonal relationships.

Cameron Sharp is an artist living in Mansfield, Ohio who uses issues of memory, time, family, and space as springboards to examine greater interpersonal relationships.